Abstract

In this paper, we will take a historical look at standardised testing, and then look at how design thinking can be applied to the issue of assessment while seeing how there is some overlap between the two.

In sections 2 and 3 we will look at the history of examinations in imperial China and in Victorian England, and how different groups have historically been underserved (and overserved) by conventional examinations. Then in sections 4 and 5, we will look at some existing prediction systems that are widely accepted, and then look at how a design approach might approach making assessment in education fairer.

1. The A-level Algorithm

In the summer of 2020 in the UK, secondary schools were closed as part of the coronavirus lockdown, and so A-level students did not sit their exams. Seeing that grades still needed to be implemented in order to allow students to progress to university, Ofqual (the government body to regulate exams) implemented an algorithm to decide what grades students would get.

Teachers provided a Center Assessed Grade (CAG) and a ranking for each student compared to their classmates. These were then combined with the school's performance over the previous three years to decide what grade each student would receive (Ehsan et al., 2022).

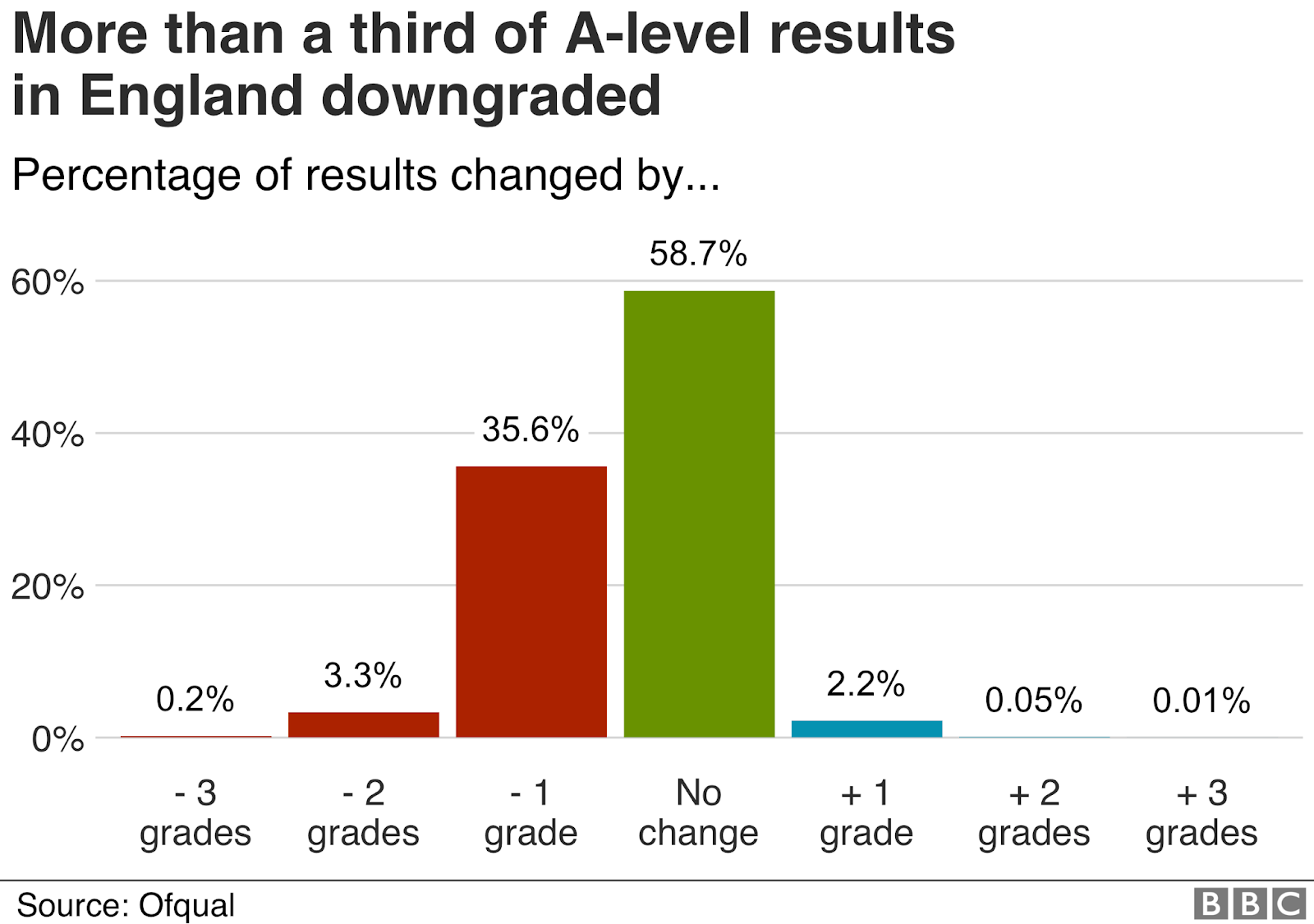

This led to almost 40% of students having a lower grade than the teacher recommended, with 3% having two grades lower than estimated (BBC, 2020). Analysis indicated that students from disadvantaged backgrounds had been hit the hardest by downgrading. A later Ofqual report showed that this was partially due to teacher-assigned grades only being given priority in classes of less than 15 students, which favoured private schools which typically could afford to have smaller class sizes. (Ofqual, 2020)

Figure 1.1 (BBC, 2020)

Protests began outside the Department of Education, with protestors chanting "f**k the algorithm". Although algorithmic decision-making is widespread these days, it is likely that it was the amount of downgrading (see Figure 1.1) and hence perceived unfairness that resulted in the protests, a phenomenon documented by Wang et al who found that "people rate the algorithm as more fair when the algorithm predicts in their favor" (Wang et al., 2020).

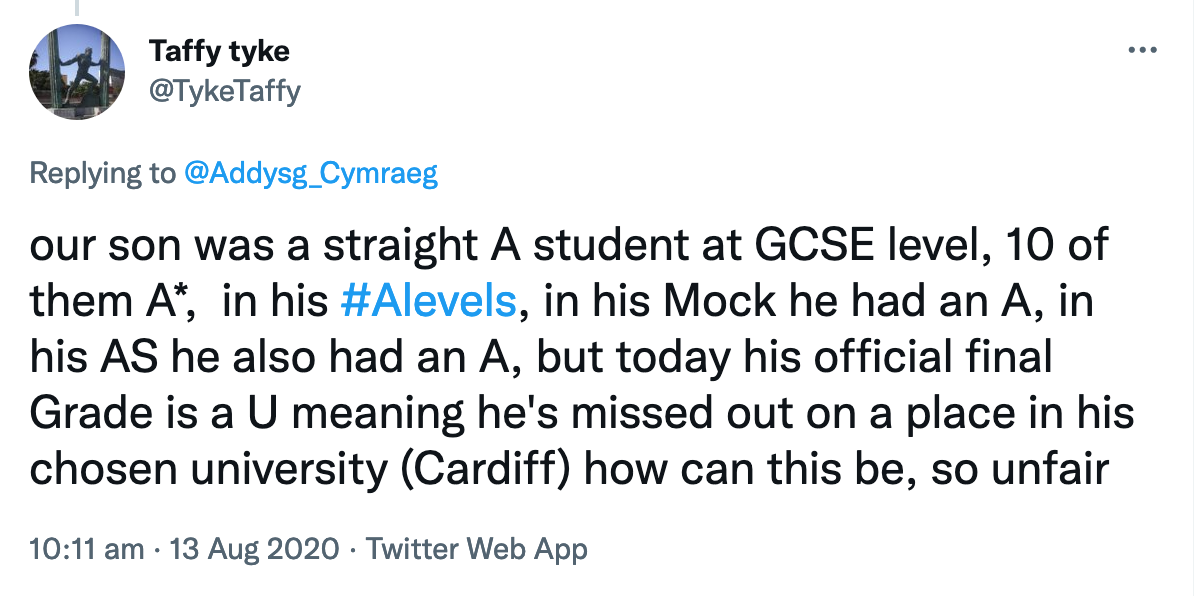

Fig 1.2 (Taffy tyke [@TykeTaffy], 2020)

The backlash led to the algorithmically-assigned grades being scrapped a week later, and students receiving their CAG grade. One thing to note was that the term "algorithm" was not widely used around the world to explain how grades would be given, for example in Bangladesh teachers were simply asked for the CAG and ranking without understanding how these would be used. Their perception was that this was a "tactic to deter criticism". (Ehsan et al., 2022)

The primary criticism was that of the algorithm being "unfair", but we must take a closer look at the educational system to see if the algorithm introduced new biases, or whether standardised examinations already resulted in these biases in the system, and the algorithm simply surfaced up what was already there.

2. History of standardised assessment

To begin with, we will look at two large-scale systems of examination to see some of the attitudes around testing that have existed historically - first briefly to the examination systems of the 7th-19th centuries in Imperial China, and then in more detail to the introduction of standardised school examinations in Victorian England in the 19th century, which pre-date modern examinations in the UK

Although standardised exams in the UK were introduced during Victorian times, we will first look back further to Imperial China, where the "imperial examination" was used in the civil service to select candidates for the state from as far back as the Sui Dynasty in the early 7th century (Miyazaki, 1981).

Learning in this system involved at least "six interrelated aspects: poetic, political, social, historical, natural, and metaphysical" and Elman points out that the examination system was well-regarded around the world - "Europeans who traveled to China in the sixteenth century marveled at the Chinese. Catholic missionaries wrote educational achievements of approvingly of the civil service examinations regularly held under government auspices." (Elman, 2013).

Iona Man-Cheong looks at the reasons why this system was so subscribed to into the late imperial rule. They argue that the exams were "crucial to the process that helped produce and reproduce a unitary, centralized state" as they were a "process that shaped candidates through the necessary disciplinary training as servants of the state" and that the system of examinations "structurally elaborated a collective identity" (Man-Cheong, 2004). Chaffee also similarly points out that the social status and legal privileges that came as a byproduct of passing exams were an important part of the acceptance of the system (Chaffee, 1995).

After over a millennium of the examination system existing in various forms throughout imperial China, in the early 20th century "the civil examinations lost their cultural luster and became the object of ridicule by literati-officials and Protestant missionaries as an “unnatural” educational regime that should be discarded", and they were abolished in the late Qing dynasty reforms in 1905.

In the UK, the Victoria era marked the beginning of standardised exams and, as Elwick points out, critics of the system introduced in the last 19th century often did so through the lens of comparison to Chinese assessment methods "Critics of this new system, such as the Oxford Assyriologist Archibald Henry Sayce, warned of an 'adopted Chinese culture'" (Elman, 2013).

The main aim for standardisation within the existing schooling system was to make students more legible to the system, and as part of that, we see the assumption that any student sitting the exams was commensurable (able to be measured by a common standard).

Historian Keith Hoskins draws on Foucaldian ideas around examinations being part of disciplinary power (Foucault, 1995) and discussed the use of examinations as instruments of measurement "it is the logical contradiction within which we are all placed by being subject to measures that are also targets, regardless of our degree of individual willingness to adopt system-beating practices" (Hoskin, 1996). This is ironic if we consider Goodhart's Law "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure" (Goodhart, 1984).

Many criticisms around the effectiveness of standardised exams abounded, such as Rothblatt's remarks about "the famous English distinction between teaching and examining" (Rothblatt et al., 1988). Trevelyan made a similar observation, comparing British examinations with those for the Indian Civil Service that produced "competition wallahs" - a derogatory term referencing the men who had simply learned to pass exams were deficient in "the social virtues of gentlemen" (Trevelyan, 1864).

An argument in favour of standardisation was that of exams raising standards overall. Elwick points out that "Reformers such as Edwin Chadwick saw pass standards as inferior to competitive standards, partly because pass standards had to be easier ... Competitive standards, by contrast, were superior because of their inherent mystery: no one knew how well one’s fellow candidates would place. This indeterminacy meant that each person had no choice but to prepare more intensely ... that is, competition lifted standards automatically, like an invisible hand" (Elwick, 2021).

Exams promised to bring about a system of meritocracy, but we can see that this is an anachronistic view considering many groups were excluded from sitting "more conservative schools such as Oxford saw certain groups of people as incommensurable –not formally admitting anyone who did not subscribe to the thirty nine articles of Anglicanism. Slightly more liberal schools such as Cambridge might allow non-Anglicans to register (like J.J. Sylvester)," but they could not obtain a degree" (Elwick, 2021).

Espeland and Stevens talk about commensuration as a "technology of inclusion" (Espeland & Stevens, 2003) and one key way that this proved true during the Victoria era was with exams providing a way for feminist movements of the time to prove their worth against men.

Elwick describes how exams were used in three key ways in the feminist movement - as surveys (providing information about female abilities), wedges (to pry open opportunities for women at other institutions), and as trials (publically demonstrating intellectual abilities compared to men) (Elwick, 2021)

In 1890, Phillippa Fawcett (daughter of prominent feminist Millicent Garrett Fawcett) placed 13 per cent above the top candidate in the Maths Tripos. She unofficially wrote the exam, but under exam conditions and so in the public mind became celebrated as the top candidate that year with even the New York Times announcing her victory, which provided a strong fact in consequent battles for women's rights (Siklos, 1990).

Elwick points out another key reason that exams were effective as a part of the feminist movement was the economic factor - "It was faster, cheaper, and easier to test twenty people using a single examination than it was to test two sets of ten people using two different exams" (Elwick, 2021).

We will see in section 3.1 how standardised testing actually swings in favour of female educational attainment to this day.

3. Intersectionality and attainment

Having taken a look at the history of standardised testing, we can see that the standardisation of exams did not necessarily mean that the commensurability of students extended to all groups of people, but that they were useful for moving forward the feminist movement. We will now take a further look at some axes of identity and how these relate to attainment, and then discuss how intersectionality plays into this.

Exams have become the infrastructure for the education system, and as D'Ignazio and Klein point out - "once a system is in place, it becomes naturalized as 'the way things are.' This means we don’t question how our classification systems are constructed, what values or judgments might be encoded into them, or why they were thought up in the first place" (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

By contemplating the role of exams, we are doing what Bowker calls "infrastructural inversion" - bringing the background (infrastructural) elements of a system to the foreground (G. Bowker & Star, 1994). Bowker and Star discuss in detail how classification systems are an essential part of working infrastructures but also how we often forget to question these parts of the system until there is a problem (G. C. Bowker & Star, 1999).

This is concerning when you consider the power that curriculums have to shape students' perspectives. As Elwick points out, examiners (and in the modern-day exam boards) deciding to accept religious beliefs over scientific answers meant students would be taught religious beliefs as a preference - "In this quiet way, Huxley and other examiners could reinforce their preferred perspectives, such as a worldview that was more naturalistic" (Elwick, 2021).

We also see a modern pushback on this in the form of the "Decolonise the Curriculum" movement, which seeks to create teaching which raises a wider range of viewpoints and actively explains that many parts of history that are taught are_one story_ of the past.

3.1 Women’s attainment

The history of women’s education has been varied, for example in Imperial China, Elman notes that "[Occupational prohibitions] kept many others out of the civil service competition, not to mention an unstated gender bias against all women." and that this attitude towards not educating women remained until the 17th century when the education of elite women became more common (Elman, 2013).

We saw in section 2 how exams were a part of the feminist movement in Victorian times, and women began sitting and excelling in exams in the Victorian era. To this day women continue to perform better in exams, although the literature around_why_ this happens is quite varied.

Gibb et al point out that "A theme that permeates all explanations is that gender differences in educational achievement are largely a reflection of gender differences in classroom behaviour" (Gibb et al., 2008). Another explanation is that of differing social attitudes to education - Warrington et al found that “boys were more likely than girls to be ridiculed by their peers for working hard at school, and frequently pretended not to care about schoolwork in order to gain acceptance from their peer group" (Warrington et al., 2000).

Literature around tracking (grouping students by ability) and female educational attainment show variance in when tracking is beneficial for girls in education. Hadjar and Buchmann showed that tracking early benefits girls with an "accumulation of advantage" (Hadjar & Buchmann, 2016), whereas Pekkarinen showed that late tracking was better for girls as it occurred at a "critical age" (Pekkarinen, 2008). Scheeren and Bol take a longitudinal perspective on this and use a differences-in-differences approach to show that both are true, but tracking later has a greater positive effect (Scheeren & Bol, 2022).

While this picture looks good for girls, they are still currently under-represented in STEM subjects. Keeves and Kotte looked at students in ten different countries in 1990 and found that male students consistently held more favourable attitudes toward science than female students, and theorised that social reasons were the cause of this change in attitude in adolescent students (Keeves & Kotte, 1990). We can see that these disparities still persist decades later (Eddy & Brownell, 2016).

3.2 Class differences and attainment

Alongside gender differences, a common complaint levied against the educational system is that it is unfair towards students from lower-class backgrounds, something which we saw as statistically true in the A-level algorithm in section 1. This is not unique to modern education, as Elman points out that in the system in imperial China "true social mobility, peasants becoming officials, was never the goal of state policy in late imperial China; a modest level of social circulation was an unexpected consequence of the meritocratic civil service" (Elman, 2013).

Raymond Boudon also spoke about educational attainment being linked to social class position, and posited a two-part model - parental expectations of educational level would differ between classes, and "positional theory" - by being too educated working-class people would alienate themselves from their peers and thus be less likely to do so (Boudon, 1976).

3.3 Intersectionality

We've talked about two axes of identity which result in educational differences here, but there are of course many others which manifest in the system. For example, Stevens presents a comprehensive review of race and educational attainment (Stevens, 2007), and Gilmour et al discuss why an achievement gap exists for disabled students, despite many policies existing to try and counteract this (Gilmour et al., 2019).

We have also been considering each of these axes as distinct things that may affect a person's education, but the reality is that intersectionality adds another layer of complexity to the reality here. The term "intersectionality" was introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Crenshaw, 1989) and it provides a lens for looking at multiple aspects of a person's sociopolitical identity and how they might combine to create discrimination and privileges.

We can see there is lots of complexity here, and not really a static rule for which groups always do better or worse within the educational system, we can only track broad trends as opposed to understanding every individual's experience. Collins and Bilge acknowledge this in their discussion on intersectionality - "Using intersectionality as an analytic tool is difficult, precisely because intersectionality itself is complex" (Collins & Bilge, 2020).

Although we can see that certain groups are broadly underserved by the current education and assessment system, it should be noted that the modern system does proactively try to counteract some of these things. For example at UK universities, contextual offers are given to acknowledge that a lower grade at a school in a low socioeconomic area can be considered on par with a top grade in a more wealthy school (UK University Search, n.d.). Many schools and universities also offer extra time in examination settings to account for people who may need it for a variety of reasons (Weale & correspondent, 2019).

This concept isn't new at all, as we can see various initiatives existed in the other systems we have explored, from extra incentives for local children in India during British rule (Elwick, 2021), to initiatives that sought to allocate higher grades equally across less prosperous regions in imperial China (Elman, 2013).

4. Existing predictive systems

Although in the case of the A-level algorithm there were widespread protests about the use of an algorithm for something so important, it should be noted that there are many other cases where algorithms are used to calculate things in the absence of information and are widely accepted as being "fair".

One example is the Duckworth-Lewis-Stern method (Stern, 2016), which is used in cricket matches to calculate a required score to win when a match has been interrupted by weather or other extenuating circumstances.

One of the reasons that the method is accepted is that, while previous methods occasionally produced outputs that were statistically impossible, the DLS method generally produces a reasonable answer, with most criticism being around how complex the actual method is to understand.

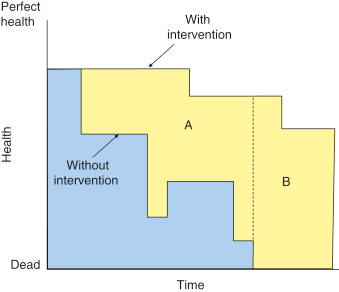

Another, and slightly more significant, method for prediction is that of quality-adjust life years (QALY), which are used as a measure of health outcome in healthcare for the economic evaluation of health interventions, looking at the quality and quantity of life after an invention

Fig 4.1 (Salomon, 2017)

Since healthcare systems have a finite amount of funding, it's used directly to decide if healthcare will be delivered or not, which in the case of some procedures is the case between life and death. Despite being such a crucial part of a person's life, it is largely accepted to use a method to decide whether an intervention will be delivered, although alternatives have been proposed, most notably the Health-Year-Equivalent (HYE) by Mehrez and Gafni (Mehrez & Gafni, 1991), which calculates utilities across multiple health states in a person's lifetime as opposed to considering each intervention independently.

There are of course also much less accepted algorithms that are still used widely, such as the hotly-debated COMPAS algorithm used to calculate a defendant's bail in the US (Corbett-Davies et al., 2016), or those used to evaluate candidate resumes in a hiring process, which have come under fire for discriminating based on ethnicity (Derous et al., 2015).

With the fact in mind that it's possible to make prediction systems with wider social acceptance, let's look at how design thinking would approach designing a more transformative assessment system.

5. Design thinking

In his book Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek discusses design as "the conscious and intuitive effort to impose meaningful order". To see how we might apply design thinking to the issue of assessment, we'll first look at a few different design methodologies - value-sensitive design, reflexive design, and participatory design, and finally, land on the "design justice" methodology as a good extension of these.

Value-sensitive design (VSD) was developed in the 1990s to attempt to counteract biased design (Friedman et al., 2002). It is an interactive process, involving multiple forms of investigation of the context and stakeholders involved in an artefact's lifetime, and recognises two stakeholder groups - direct stakeholders (those who directly interact with a technology), and indirect stakeholders (those who experience ancillary effects) (Umbrello, 2021)

Participatory design (PD) takes the same concept of looking at bias in design and, inspired by its roots in Scandinavian trade unions (Costanza-Chock, 2020), it seeks to include marginalised voices in the design process. As Jutta Treviranus points out, "people at the margins are the first to feel the effects of flaws in the system, as well as crises to come" (Treviranus, 2021), so they will be able to provide a more relevant viewpoint to the design process than designers who are more removed from the use case of a technology.

While both of these approaches have their pros, there are some key criticisms of VSD and PD to consider. While VSD works to counteract bias. which is what we'd like for our system, Costanza-Chock points out its most potent criticism "VSD is descriptive rather than normative: it urges designers to be intentional about encoding values in designed systems but does not propose any particular set of values at all" (Costanza-Chock, 2020).

It also assumed that values will stay consistent over time and that new values won't be revealed over time, which when we consider that our ideas around "fairness" for different groups have changed over time, may mean that a technology does not stand up well to the test of time. Spiekermann and Winkler point out a similar issue - "future contexts of many of their systems can only be anticipated to a limited degree" (Spiekermann & Winkler, 2020).

Selbst et al also detail some "abstraction traps" with modelling systems around values - inadequately modelling the existing system, failing to understand how a solution can do harm in a different context than intended, failing to account for the full meaning of social concepts, not considering reflexivity when inserting technology into a social system and focussing on tech solutionism (Selbst et al., 2019).

With this in mind, we may look to the more prescriptive PD approach. One of the good aspects of it is that it includes a reflexive design approach, which involves the designers themselves also evaluating their own roles and relationships in the process. However, Fish and Stark identify some key limitations of the reflexive design approach, which they present through "four reflexive values–value fidelity, appropriate accuracy, value legibility, and value contestation" (Fish & Stark, 2021).

Costanza-Chock also points out that many times while using PD the wider context of a system's usage tends to be lost - "The Nordic approach to PD is also characterized by an emphasis on the normative value of democratic decision making in the larger technological transformation of work … However, in the US context, this broader concern is often lost in translation" (Costanza-Chock, 2020).

Having seen some of the key cons of using VSD and PD approaches, we will move forward with Costanza-Chock's recent proposal for a "design justice" approach. In design justice, practitioners "choose to work in solidarity with and amplify the power of community-based organizations". This is intended to counteract what often happens with PD where marginalised groups are consulted, but the power to make key choices still lies with the designers (Costanza-Chock, 2020).

The full set of design justice principles can be found in Appendix A, but we will point out some of the key aspects we might include in a transformative assessment system, and tie them back to a specific design justice principle.

5.1 Situating in context

Principle 6 - everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience

We want to avoid Nagel's "view from nowhere" (Nagel, 1989) and instead situate assessment systems in their context - real people and real lives. This is echoed in black feminist thought, which "emphasizes the value of situated knowledge over universalist knowledge" and at the same time "explicitly recognizes that knowledge developed from any particular standpoint is partial knowledge" (Costanza-Chock, 2020). As D'Ignazio and Klein point out - "by pooling our standpoints—or positionalities—together, we can arrive at a richer and more robust understanding of the world" (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020).

Looking at a wider context also includes accounting for different cultures. We see for example in the case of the A-level algorithm, which impacted students in multiple countries around the world who also sit British exams, that cultural context was lost around how assessment prior to exams was considered since students there "typically take it easy in the school during the year and ramp up studying in the last few months" (Ehsan et al., 2022). We can look further back as well to see a similar situation with Indian students in Victorian times studying for British exams and mixups around student ages due to cultural differences "In India, when someone attested they were eighteen, it meant that on their birthday they had completed their eighteenth year of life. In Britain (where a birthday denoted the start of a new year of life), that same person would be counted as seventeen. In 1868, using this British convention to misinterpret the ages given on candidates’ certificates, the commissioners ruled that four South Asian candidates were over twenty-one and therefore too old to write the exams" (Elwick, 2021).

5.2 Treating people as individuals

Principle 2 - center the voices of those who are directly impacted

Philosopher Yaron Ezrahi talks about how tasks can only be assessed against a shared standard by being viewed as detached from a person and their “inaccessible subjective dimensions” (Ezrahi, 1990). A data feminist view states that "data are not neutral or objective. They are the products of unequal social relations, and this context is essential for conducting accurate, ethical analysis." (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020) and Yanni Loukissas takes a similar approach with his idea of "data settings", referencing the fact that the surrounding processes of data collection affect what information is captured (Loukissas, 2019).

We might try to centre students' individuality by allowing multiple ways of assessment to account for those who don't do their best in written exams, or by doing away with a set of grades and instead presenting a more generalised dataset about a student (Taylor, 2022).

5.3 Autonomy

Principle 8 - sustainable, community-led and -controlled

Looking at the case of students in Bangladesh with the A-level algorithm, they commented that they felt "helpless and voiceless", and that they were “robbed of the agency to build [their] own future". (Ehsan et al., 2022).

Self-determination theory (Ryan et al., 2009) proposes that autonomy must be satisfied to foster well-being and human flourishing, and so we might try to put more power into the hands of teachers and students to decide what assessment would look like.

One historical example of this was during Victorian botany exams which, when held outside of the UK, had to account for certain plants not growing in the local area "When new London exam centres were added [abroad] … a local botanist would be recruited, and London would send him a list of examinable specimens. He would then modify the list to fit the ones actually found there" (Elwick, 2021).

5.4 Including marginalised students

Principle 1 - sustain, heal, and empower

Elwick notes that the Revised Code in 1867 by Edward Arnold that moved from reporting best students to reporting percentage pass rates at schools served to push teachers "to also focus on the quiet children who were easy to overlooking" (Elwick, 2021),

In this same way, we could focus on bringing their attainment upwards for students who are most being underserved by the current system, which is likely to also result in a positive shift for other students.

A key way that could seek to remove bias of all forms from marginalised students is anonymisation, which is something that we would want to preserve from the existing system of examinations, where papers are marked with only an identification "number" rather than a name. Elwick points out that Frances Buss, headmistress of the North London Collegiate School for Girls, favoured the same system - "Buss favoured exams that used identification numbers, or even first initials, rather than full names” (Elwick, 2021).

5.5 Transparency

Principle 4 - change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process

As D'Ignazio and Klein point out "Disclosing your subject position(s) is an important feminist strategy for being transparent about the limits of your—or anyone’s—knowledge claims" (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020) and adding transparency to any assessment system is an important part of providing informed autonomy to any party in the system.

This was lacking in the case of the A-level algorithm for teachers in Bangladesh, where many teachers expected the algorithm to "intelligently bump [their] TAGs because [they] always gave lower marks on mock exams to motivate the student to study harder" (Ehsan et al., 2022). Lack of transparency there meant that they weren't able to properly assess how their actions would work within the system.

It should be noted however that explainability of complex systems can be extremely hard. Goodman and Flaxman discuss the issues with algorithmic transparency laws in terms of how common-machine learning processes don't produce information about their decision-making that is understandable to the average person (Goodman & Flaxman, 2017). In this same way, we would need to be careful to ensure that explanations of decisions within the system are understandable to humans.

We can see that a design justice approach addresses some key criticisms of VSD and PD, and applying design-thinking to designing transformative assessment system yields some key aspects that could be included, and that some of these tie back to things that have historically already been included in examinations, such as anonymisation and allowing localisation.

Conclusion

We saw that a historical look at exams showed how standardised examinations existed for many centuries in imperial China as a respected institution, and how in Victoria times they were adopted as a way of making students more legible, with the unintended side effect of aiding the feminist movement of the time. We also took a look at some groups which still saw an attainment gap, and that intersectionality was also at play in the education system.

Taking a design approach to assessment, it was clear that some aspects of historical examinations such as continuing to anonymise students when marking, but others would change, such as centering the voices of international students more and giving more autonomy to local centres.

Appendix

A - Design Justice Principles

- We use design tosustain, heal, and empowerour communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

- Wecenter the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

- Weprioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

- We viewchange as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

- We see the role of thedesigner as a facilitator rather than an expert.

- We believe thateveryone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

- Weshare design knowledge and tools with our communities.

- We work towardssustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

- We work towardsnon-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

- Before seeking new design solutions,we look for what is already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

Bibliography

BBC. (2020, August 20). A-levels and GCSEs: How did the exam algorithm work?BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/explainers-53807730

Boudon, R. (1976). Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. By Raymond Boudon. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1973. Pp. v, 220. $12.50.).American Political Science Review,70(2), 605–605. https://doi.org/10.2307/1959667

Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (1999).Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. MIT Press.

Bowker, G., & Star, S. (1994).Bowker, G." Information Mythology and Infrastructure.» In Information Acumen: The Understanding and Use of Knowledge in Modem Business, edited by L. Bud.

Chaffee, J. W. (1995).The Thorny Gates of Learning in Sung China: A Social History of Examinations, New Edition. State University of New York Press.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020).Intersectionality, 2nd Edition (2nd edition). Polity.

Corbett-Davies, S., Pierson, E., & Goel, S. (2016, October 17). A computer program used for bail and sentencing decisions was labeled biased against blacks. It’s actually not that clear.Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/10/17/can-an-algorithm-be-racist-our-analysis-is-more-cautious-than-propublicas/

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020).Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. MIT Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989).Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429500480-5

Derous, E., Ryan, A. M., & Serlie, A. W. (2015). Double Jeopardy Upon Resumé Screening: When Achmed Is Less Employable Than Aïsha.Personnel Psychology,68(3), 659–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12078

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020).Data Feminism. MIT Press.

Eddy, S. L., & Brownell, S. E. (2016). Beneath the numbers: A review of gender disparities in undergraduate education across science, technology, engineering, and math disciplines.Physical Review Physics Education Research,12(2), 020106. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020106

Ehsan, U., Singh, R., Metcalf, J., & Riedl, M. O. (2022). The Algorithmic Imprint.2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 1305–1317. https://doi.org/10.1145/3531146.3533186

Elman, B. (2013).The civil examination system in late imperial China, 1400-1900.8, 32–50. https://doi.org/10.3868/s020-002-013-0003-9

Elwick, J. (2021).Making a Grade: Victorian Examinations and the Rise of Standardized Testing. University of Toronto Press.

Espeland, W., & Stevens, M. (2003). Commensuration as Social Process.Annual Review of Sociology,24, 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.313

Ezrahi, Y. (1990).The Descent of Icarus: Science and the Transformation of Contemporary Democracy. Harvard University Press.

Fish, B., & Stark, L. (2021). Reflexive Design for Fairness and Other Human Values in Formal Models.Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1145/3461702.3462518

Foucault, M. (1995).Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (2nd Vintage Books ed). Vintage Books.

Friedman, B., Kahn, P., & Borning, A. (2002). Value sensitive design: Theory and methods.University of Washington Technical Report,2, 12.

Gibb, S. J., Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2008). Gender Differences in Educational Achievement to Age 25.Australian Journal of Education,52(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410805200105

Gilmour, A. F., Fuchs, D., & Wehby, J. H. (2019). Are Students With Disabilities Accessing the Curriculum? A Meta-Analysis of the Reading Achievement Gap Between Students With and Without Disabilities.Exceptional Children,85(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402918795830

Goodhart, C. A. E. (1984). Problems of Monetary Management: The UK Experience. In C. A. E. Goodhart (Ed.),Monetary Theory and Practice: The UK Experience (pp. 91–121). Macmillan Education UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-17295-5_4

Goodman, B., & Flaxman, S. (2017). European Union regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a ‘right to explanation’.AI Magazine,38(3), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v38i3.2741

Hadjar, A., & Buchmann, C. (2016).Education systems and gender inequalities in educational attainment. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t892m0.14

Hoskin, K. (1996). The ‘awful idea of accountability’: Inscribing people into the measurement of objects.Accountability : Power, Ethos and the Technologies of Managing / Edited by Rolland Munro and Jan Mouritsen.

Keeves, J., & Kotte, D. (1990). Disparities Between the Sexes in Science and Scientists.Science Education,84(2), 180–192.

Loukissas, Y. A. (2019).All Data Are Local: Thinking Critically in a Data-Driven Society. MIT Press.

Man-Cheong, I. (2004).The Class of 1761: Examinations, State, and Elites in Eighteenth-Century China. Stanford University Press.

Mehrez, A., & Gafni, A. (1991). The Healthy-years Equivalents.Medical Decision Making : An International Journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X9101100212

Miyazaki, I. (1981).China’s Examination Hell: Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China: The Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China (C. Schirokauer, Trans.; Revised ed. edition). Yale University Press.

Nagel, T. (1989).The View From Nowhere (Revised ed. edition). Oxford University Press.

Ofqual. (2020).Awarding GCSE, AS, A level, advanced extension awards and extended project qualifications in summer 2020: Interim report. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/awarding-gcse-as-a-levels-in-summer-2020-interim-report

Pekkarinen, T. (2008). Gender Differences in Educational Attainment: Evidence on the Role of Tracking from a Finnish Quasi-Experiment.The Scandinavian Journal of Economics,110(4), 807–825.

Rothblatt, S., Muller, D. K., Ringer, F., Simon, B., Bryant, M., Roach, J., Harte, N. B., Smith, B., & Symonds, R. (1988). Supply and Demand: The ‘Two Histories’ of English Education.History of Education Quarterly,28(4), 627. https://doi.org/10.2307/368852

Ryan, R. M., Williams, G. C., Patrick, H., & Deci, E. L. (2009). Self-determination theory and physical activity: The dynamics of motivation in development and wellness.Hellenic Journal of Psychology,6(2), 107–124. Scopus.

Salomon, J. A. (2017). Quality Adjusted Life Years. In S. R. Quah (Ed.),International Encyclopedia of Public Health (Second Edition) (pp. 224–228). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00368-4

Scheeren, L., & Bol, T. (2022). Gender inequality in educational performance over the school career: The role of tracking.Research in Social Stratification and Mobility,77, 100661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100661

Selbst, A. D., Boyd, D., Friedler, S. A., Venkatasubramanian, S., & Vertesi, J. (2019). Fairness and Abstraction in Sociotechnical Systems.Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287560.3287598

Siklos, S. (1990).Philippa Fawcett and the Mathematical Tripos. Newnham College.

Spiekermann, S., & Winkler, T. (2020).Value-based Engineering for Ethics by Design (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3598911). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3598911

Stern, S. E. (2016). The Duckworth-Lewis-Stern method: Extending the Duckworth-Lewis methodology to deal with modern scoring rates.Journal of the Operational Research Society,67(12), 1469–1480. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2016.30

Stevens, P. A. J. (2007). Researching Race/Ethnicity and Educational Inequality in English Secondary Schools: A Critical Review of the Research Literature Between 1980 and 2005.Review of Educational Research,77(2), 147–185. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430301671

Taffy tyke [@TykeTaffy]. (2020, August 13).@wgmin_education our son was a straight A student at GCSE level, 10 of them A*, in his #Alevels, in his Mock he had an A, in his AS he also had an A, but today his official final Grade is a U meaning he’s missed out on a place in his chosen university (Cardiff) how can this be, so unfair [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/TykeTaffy/status/1293837655516618752

Taylor, R. (2022, June 22).Roger Taylor: Informal Conversation.

Trevelyan, S. G. O. (1864).The Competition Wallah. Macmillan.

Treviranus, J. (2021, May 10). Designing for the edges.Offscreen Magazine,24.

UK University Search. (n.d.).What Are Contextual Offers? UK University Search. Retrieved 6 July 2022, from https://www.ukuniversitysearch.com

Umbrello, S. (2021, July 1).Value Sensitive Design with Steven Umbrello. https://www.machine-ethics.net/podcast/vsd-with-steven-umbrello/

Wang, R., Harper, F. M., & Zhu, H. (2020). Factors Influencing Perceived Fairness in Algorithmic Decision-Making: Algorithm Outcomes, Development Procedures, and Individual Differences.Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376813

Warrington, M., Younger, M., & Williams, J. (2000). Student Attitudes, Image and the Gender Gap.British Educational Research Journal,26(3), 393–407.

Weale, S., & correspondent, S. W. E. (2019, November 21). One in five GCSE and A-level pupils granted extra time for exams.The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/nov/21/one-in-five-gcse-and-a-level-pupils-granted-extra-time-for-exams