Intro

In this paper we will explore the use of AI for content moderation at Meta's Facebook and how we might go about governing this effectively. Starting with first considering how social media sites should be analysed, we will then look at the power that they hold. Then in the second half of this paper, we will look at how AI is used for content moderation at Facebook, Meta's response to various regulation efforts and social issues, and whether other forms of governance may be more effective in making sure the use of AI for content moderation at Facebook is appropriate.

How should we consider social media sites?

The term 'platform' is often used to describe digital systems, in particular in terms of 'social media platforms'. But this word itself often comes loaded with certain connotations. Schwarz describes a platform in an architectural sense "a platform is a digital infrastructure intended for users to apply either computer code in the conventional sense, or to apply a set of human uses", but van Dijck describes platforms in a more relational sense, focussing on platforms as a "set of relations that constantly needs to be performed" by various stakeholders such as users and creators of the platform (Van Dijck, 2013).

Gillespie provides an analysis of the semantics of the word 'platform' itself and what it has signified in the past - computation (technical), architectural (a raised surface in a building), figurative (as a foundation), political (a candidate's views) (Gillespie, 2010). Through this, they show that companies creating digital platforms have introduced a more broad meaning of the term in order to appeal to a wide variety of stakeholders simultaneously.

There is also implied programmability when it comes to platforms around what kind of interactions are possible, which as Gorwa points out can be traced all the way back to "California in the 1990s, as software developers began to conceptualize their offerings as more than just narrow programmes, but rather as flexible platforms that enable code to be developed and deployed" (Gorwa, 2019b).

In a digital sense, this is often present in the form of APIs (application processing interfaces), which many digital services provide to integrate into their systems. Andreesen presents three levels of programmability of software platforms - the "Access API" to access data and functionality of a platform in a structured way, the "Plug-In API" to plug into more of the functionality of the core system and the "Runtime Environment" where developers can run a full application inside the system (Andreessen, 2007). These three levels show us that there are varying levels of power and control that a company can give others over its platforms, and Helmond places APIs at "the core of the shift from social network sites to social media platforms". Many scholars characterise platforms around this ability to move data around, such as Liu's idea of "data pours" which enable data to flow around platforms and to third parties (Liu, 2004), so it may sound as though programmability and data access are key aspects of platforms. But this programmability also allows users to easily move data off the platform and begin using competitors' products, and so as Plantin et al. note "achieving lock-in is among platform builders’ principal goals" (Plantin et al., 2018), so there is a strong incentive for developers to provide limited or no programmable access to their platforms.

"Platform" is common terminology but others use the term 'network' for the same phenomena of the rise of social media sites and thus focus on a more infrastructural viewpoint. Sandvig discusses how considering the internet as an infrastructure allows us to better understand how technical changes can have "unanticipated and unintended societal consequences" and characterises five attributes of an infrastructure that the web clearly demonstrates: invisibility, dependence on human practices, modularity, standardization, and momentum (Sandvig, 2013).

As platforms look at APIs and modularity, so too do infrastructure look at connections, but instead media studies scholars often consider infrastructures as a set of relations as opposed to a set of components (Bowker & Star, 1994; Star & Ruhleder, 1994), and also think about these relations as "an infinite regress of relationships" in which an infrastructure's parts can always be broken down further. When we consider how complex many digital platforms are, and how many layers of computing and process they are built on, it is clear that an infrastructural look can be a useful way of considering digital platforms.

So should we consider social media sites as platforms or as infrastructures? Scholars in recent years have spoken about the increasing "platformization" (Helmond, 2015) and the "platform society" (Van Dijck et al., 2018) as platforms become the dominant model for the social web. However, we can see that infrastructure is also a suitable term for social media sites considering how pervasive they are and the strong relationality involved.

Plantin et al. discuss how the boundaries between "platform" and "infrastructure" are becoming blurry as digital technologies "have made possible a 'platformization' of infrastructure and an 'infrastructuralization' of platforms" (Plantin et al., 2018).

Going forward we will be considering social media sites (in particular focussing on Meta's "Facebook") as both platforms and infrastructures, and the literature certainly backs up this view since scholars have considered Facebook as both a platform (Helmond, 2015) and an infrastructure (Plantin et al., 2018).

The power of social media platforms

With the rise of the internet came a variety of different types of sites, and one of those were social network sites, which boyd traces back to the "first recognizable social network site "SixDegrees.com, which users to "create profiles, list their Friends and, beginning in 1998, surf the Friends lists" (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). From this we see a varied history of different social network sites springing up, and the creation of Facebook is well-documented from its start in 2004 as a Harvard-only site to the following years of moving to a globally-used site (Kirkpatrick, 2011).

The power of social media

Scholarship explores the sheer power that social media platforms have on society by virtue of their size and reach, pointing out how social media sites are becoming increasingly used as sources for news, entertainment and communication (Newman et al., 2018), and van Dijck and Poell talk about the concept of "social media logic" - the programmability and user participation in social media alongside the surveillance and datafication that is perpetuated by the creators of those platforms (Van Dijck & Poell, 2013).

Most notable in their power is that social media platforms are able to decide what their users can access and what content they see. Cobbe establishes how through algorithmic censorship, social platforms "unilaterally position themselves as both the mediators and the active, interventionist moderators of online communications in a way that would otherwise be impossible" (Cobbe, 2021).

Scholars note how platforms often position themselves as intermediaries that are neutral and that the public perception often views algorithms as acting on their own accord, but in fact, these platforms contain a logic around formatting data and deciding what to present to users (Gillespie, 2015; Helmond, 2015; Van Dijck, 2013). As Gillespie notes "Social media platforms don’t just guide, distort, and facilitate social activity—they also delete some of it. They don’t just link users together; they also suspend them. They don’t just circulate our images and posts, they also algorithmically promote some over others" (Gillespie, 2015)

Being digital systems, social media platforms can also be thought of as having a form of "binary control" that is inherent to digital code. As Lessig famously observed - "code is law" (Lessig, 2009), and this manifests on platforms when looking at how certain content is outright banned rather than considering each case in a nuanced way.

Scholars and journalists alike note how social media has a power so great that it pushes outwards to other parts of the internet's ecosystem. In particular, Helmond points out how the rise of social media and the provided programmability means that webmasters have to embed code onto their websites to make them "platform ready', and explores the "double logic of platformization" - social media platforms extending to the rest of the web, and also their drive to make other parts of the web data ready for them (Helmond, 2015).

This power is also exerted onto other large entities, such as the media industry, who can find themselves in danger of losing access to their data and revenue from their social media presence (Kleis Nielsen & Ganter, 2018), and many have characterised this consolidation of power to just a few social media companies as a "tech oligarchy" (Andriole, n.d.) and voiced their concerns around their lobbying power and how "these companies could grow so large and become so deeply entrenched in world economies that they could effectively make their own laws" (Manjoo, 2016).

Part of why this amalgamation of power is so concerning is the fact that the creators of social media platforms are companies and not public institutions, so they are ultimately incentivised to shape participation in ways that will allow them to make a profit. Schwarz considers these by looking at the affordances of the platforms and how these can be "prescriptive" or "restrictive" modes of control, i.e. they can define a space of possible actions that a user can take on the platform (Andersson Schwarz, 2017).

We can see that social media companies possess a lot of power in society, but they typically tend to downplay this, with the bigger platforms trying to characterise themselves as "open" and "free" platforms that merely facilitate public expression rather than guide it. As Atal points out, the debates around platform companies as "stewards of a new public sphere" often take these platforms' neutrality for granted, which completely ignores the power and control that these platforms enact. They also note how companies use their straddling as "product companies, service companies and infrastructure companies" to counteract being regulated and continue their control (Atal, 2020). Gillespie also notes this phenomenon and presents a case study of YouTube using the term "platform" to "position themselves as neutral facilitators and to downplay their own agency" (Gillespie, 2010).

The power of Facebook

Looking at Facebook in particular, we see that this power is very much present in the scale and reach of Facebook. With the launch of its "Free Basics" program in 2014, which aimed to provide widespread internet access in developing nations, The program has only served to increase its monopolistic power, and as many people note - "Across Africa, Facebook_is_ the internet" (Malik, 2022), and "With an over 60% share of all social media transactions worldwide, Facebook looks more and more like a de facto infrastructure." (Plantin et al., 2018). However, the program is not without criticism and has faced concerns about its implications for data privacy and net neutrality (Sen et al., 2017), which in India resulted in the program being banned completely in 2016 (Vincent, 2016).

As other social media platforms do, Facebook also exerts a lot of control over what people see, in particular when it comes to their feed's EdgeRank algorithm (Langlois & Elmer, 2013) and its advertising algorithms. This most famously came to light in 2018's Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which Facebook ads were revealed to have been used in the 2016 US elections in order to have "users go 'down the rabbit hole' by following ads, carefully 'breadcrumbed' across different sites and spread by their friends and others 'like them'" (‘Correlating Eugenics (Chapter 1)’, 2021).

Notable in the power that Facebook's creator company Meta holds, is that they own multiple large social media and communication platforms - Facebook, Instagram and Whatsapp, and this gives them unique leverage in terms of "integrating them both horizontally and vertically" (Van Dijck et al., 2021), i.e. they can easily flow data between the platforms to shape user behaviour even further.

Governance

With this increasing power of social media platforms, the calls for stronger external governance have also increased in the last decade. Several definitions for governance crop up in the literature, such as Foucault's understanding of governance as "structuring the possible field of action of others" (Foucault, 1982). But here we will consider a more classical idea of governance in terms of rules and guidelines enacted by the state - "a state’s ability to build functional and effective institutions and use those institutions to maintain law and order" (Gorwa, 2019b).

Governing social media

When considering the landscape of governing social media platforms, Abbot and Snidal's "governance triangle" for considering governance schemes can be useful as they present three groups of actors "firms', "NGOs" and "states" to consider (Abbott & Snidal, 2021). However for social media, it should be noted that governance also impacts what Poell, Van Dijck, and Nieborg call 'complementors' - other parties that participate in the platform's ecosystem such as advertisers, app developers, gig workers, cultural content producers (Nieborg & Poell, 2018; Poell et al., 2018).

Currently, social media platforms are still largely self-governing, but the move towards more state intervention is clear (Helberger et al., 2018). Gorwa comments that government intervention around platforms is "catalyzing around three policy levers: the implementation of comprehensive privacy and data protection regulation, the repudiation of intermediary liability protections, and the use of competition and monopoly law" (Gorwa, 2019b).

Many people are also sceptical of the current self-governance of these platforms, pointing out that "recent transparency initiatives are predominantly public-facing, providing useful tools for journalists and interested members of the public, but arguably much less useful information for regulators and investigators" (Gorwa, 2019b), and that firms often develop self-regulatory initiatives as more of a way to improve their public relations and try to evade state regulation, as opposed to actually trying to effectively regulate (Abbott & Snidal, 2021).

However, others point out that there are actually incentives for platforms to self-regulate effectively even without external governance - lots of governance seeks to regulate the_content_ on these platforms, and the companies running these sites stand to benefit from having more regulated content on the platform so as to not scare off new users and lose the economic benefit of userbase-growth (Gillespie, 2017).

Issues in governing social media

There are some key issues when it comes to governing social media, one of the key ones being that large social media platforms operate internationally and so don't fall neatly under the jurisdiction of just one state, “the state-based system of global governance has struggled for more than a generation to adjust to the expanding reach and growing influence of transnational corporations.” (Ruggie, 2007). Some countries have tried to solve this by creating laws based on the physical location of data and users, such as the GDPR which is applicable to any company that offers services to users based in the EU. The Russian government has gone a step further by requiring platforms with Russian users to store those users' data on servers in Russia, although as Gillespie points out there may also be a selfish motive there as "housing the data inside of Russia’s borders would make it easier for the government to access that data and squelch political speech" (Gillespie, 2017).

More generally, the rate of innovation in the tech industry has proven to be much faster than that of other regulated sectors, and governments have struggled to keep up with this pace, with older digital laws such as those around "safe harbor" and takedown measures for search engine not being very applicable to newer technologies (MacKinnon et al., 2015). Many point out that social platforms are very black-boxed and hard for regulators to understand from the outside, with private intermediaries having low transparency around their data and processes, and not providing access for regulators to assess the impact of their policies (Gorwa, 2019a; Suzor et al., 2018).

A twist in state regulation of social media platforms is also that the state itself does not necessarily have an incentive to regulate these platforms since they also stand to benefit from using them, for example in their election campaigns as we discussed earlier. As Atal notes - many countries such as China and the US also rely on large tech platforms as a source of intelligence on their citizens and on other countries, and use the surveillance that these platforms can provide for their own ends (Atal, 2020).

Automated content moderation at Facebook

Having discussed the scale and impact of social media platforms, and some of the issues around regulating them, we will now look towards a specific use-case of artificial intelligence in a social media platform - AI being used for content moderation at Facebook.

With hosting user-generated content comes the risk of hosting inappropriate content, "platforms must constantly police the pornographic, the harassing, and the obscene. There is no avoiding it entirely." (Gillespie, 2017). Facebook has come under fire for hosting politically-motivated content, and an independent report in 2018 about Facebook's impact on human rights in Myanmar concluded that they were not "doing enough to help prevent our platform from being used to foment division and incite offline violence" (Meta, 2018c).

With these things in mind, we can see that Facebook has a strong need to moderate content on the platform, and in recent years the company has turned to AI as a solution to having to moderate such a large amount of content. In 2020 they revealed "AI now proactively detects 94.7 percent of hate speech we remove from Facebook, up from 80.5 percent a year ago and up from just 24 percent in 2017." (Meta, 2020b). It should be noted that the use of AI here shows that content on Facebook's platform is now being stored and used to train machine learning tools, something that human moderation was not particularly able to do (Siapera & Viejo-Otero, 2021).

Issues with automated content moderation at Facebook

Content moderation can largely be seen as a good thing for users of the platform, as Langvardt says, content moderation "makes the Internet’s ‘vast democratic forums’ usable", however, there are some major concerns when it comes to content moderation on Facebook.

Facing criticism over how conservative news items were being devalued under the manual curation of "trending" news items, Facebook switched back to an algorithm-only process, and "in turn opened the door to the controversy over fake news" (Kreiss & McGregor, 2018). In leaked audio of a Q&A with employees, CEO of Meta Mark Zuckerberg declared "We’ve made the policy decision that we don’t think that we should be in the business of assessing which group has been disadvantaged or oppressed, if for no other reason than that it can vary very differently from country to country ... we’re going to look at these protected categories, whether it’s things around gender or race or religion, and we’re going to say that that we’re going to enforce against them equally.” (Newton, 2019).

However, this approach does not at all take into account that Facebook has "already 'inherited' the unfair and unjust ways in which historically oppressed groups are treated." (Siapera & Viejo-Otero, 2021) and that censoring equally will just result in society's existing biases continuing to be perpetuated.

Siapero and Viejo-Otera argue that Facebook's content governance turns hate speech from a question of ethics, politics, and justice into a technical and logistical problem and socialises users into conduct that is akin to a "flexible racism" (Siapera & Viejo-Otero, 2021). Cobbe shows the same in the wider social platform ecosystem, arguing that "the result of algorithmic censorship, at its most effective, would be homogenised, sanitised social platforms mediating commercially acceptable communications while excluding alternative or non-mainstream communities and voices from participation" (Cobbe, 2021).

Other concerns around Facebook's content moderation strategy also arise, including a disregard for privacy that likens Facebook to a "digital gangster" (UK Parliament, 2019), accusations of Facebook making too many decisions for the user and producing a form of "technocentric equality" (Lianos, 2012), and moderation quality severely lacking when it comes to non-English content (Garton Ash et al., 2019).

Looking outside of the Facebook context, there is also wider discussion around whether AI can ultimately be a good solution for content moderation, considering that truly effective moderation will require understanding nuance. Gillespie notes his scepticism around the AI moderation systems used for Facebook because of the fluidity and adaptability of users creating content on the platform (Gillespie, 2018), and even Zuckerberg has admitted that it is "easier to build an AI system to detect a nipple than what is hate speech" (Snow, 2018).

External governance of Facebook’s AI moderation

There is currently relatively little direct regulation of Facebook's use of AI for content moderation, but in the last few years, there have been some recommendations released, such as the 2018 Santa Clara Principles for transparency and accountability in content moderation, which provide specific recommendations for how firms can implement best practices for notices and appeals around content moderation (Santa Clara Principles, 2018). A year later, a collaboration between Oxford and Stanford Universities produced a report detailing "Nine Ways Facebook Can Make Itself a Better Forum for Free Speech and Democracy", of which several recommendations dealt with how to improve content moderation - "Establish regular auditing mechanisms", "Create an external content policy advisory group", "Establish an external appeals body" (Garton Ash et al., 2019).

With the implementation of the NetzDG (colloquially termed the "Facebook Act" ) which puts hard time limits on how long illegal content can stay up, and the GDPR which enforces strict rules around data protection and privacy, the stage has been set for other regulation around the world to set rules around how social media platforms can operate. Within the next few years, there is more regulation incoming, with "government regulation, spanning changes in intermediary liability provisions, data protection laws, antitrust measures, and more, are on the horizon" (Garton Ash et al., 2019).

Facebook's responses to regulation

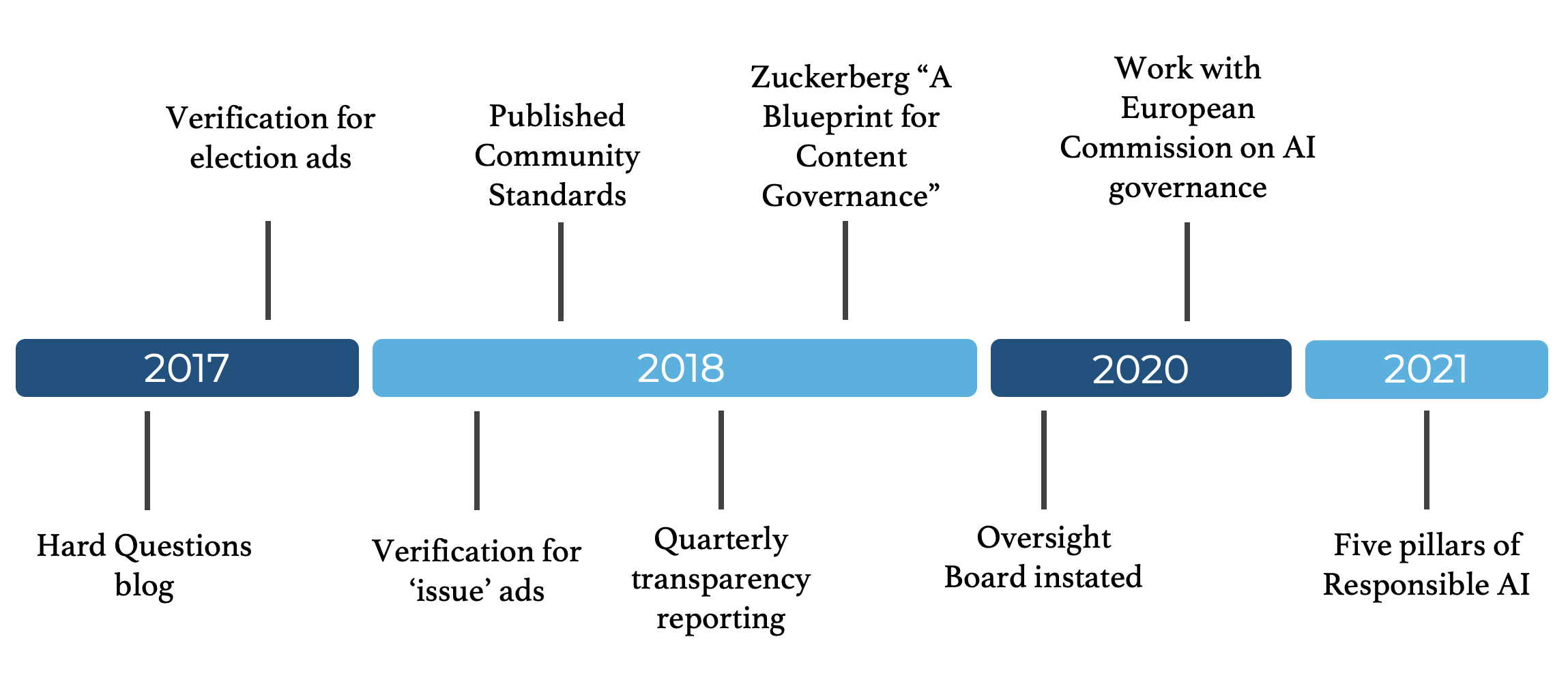

In response to the rise of regulation, Meta has argued that Facebook's scale means that they provide a public service, and hence should not be regulated, since "any constraints on its product constituted a violation of free speech principles and ‘digital equality,’" (Atal, 2020). However, they have implemented a number of new features and processes for Facebook over the years (illustrated in Figure 1).

In June 2017, Facebook started the Hard Questions blog, where they aimed to discuss complex issues around content moderation and give some insights into their moderation process (Meta, 2017).

In October 2017, Facebook started requiring users running election-related advertising to verify their identity and began to show a "Paid for by" disclosure alongside these ads. Part of this change included "building machine learning tools that will help us find them and require them to verify their identity" (Goldman, 2017). In April 2018, Facebook broadened out this policy to include "issue ads", and this change also included a corresponding update to investing in AI solutions to catch people trying to circumvent these checks, although Facebook themselves stated "We realize we won’t catch every ad that should be labeled, and we encourage anyone who sees an unlabeled political ad to report it", showing that there was still a need for humans in at least some part of the moderation process at that point (Meta, 2018a).

In April 2018, for the first time, Facebook published a detailed version of its standards to the public (Meta, n.d.-b), which included many details about what content was and wasn't allowed to stay published on the platform. Soon after this, Facebook also released their first transparency report (now published quarterly as a "Community Standards Report" (Meta, n.d.-a)), which detailed different types of content takedowns, and notably - aggregate data on just how many pieces of content were removed.

In November 2018, Zuckerberg published "A Blueprint for Content Governance and Enforcement", in which he stated "I've increasingly come to believe that Facebook should not make so many important decisions about free expression and safety on our own" and spoke about plans to "create a new way for people to appeal content decisions to an independent body, whose decisions would be transparent and binding" (Zuckerberg, 2021). Following this, in May 2020 the first members of the Facebook Oversight Board were instated (Clegg, 2020), and as of January 2023, the board has published 33 detailed case decisions from various cases around the world (Oversight Board, n.d.).

In the last few years, Facebook has also made some moves specifically around AI governance, including beginning work with the European Commission on AI governance in June 2020 (Meta, 2020a), and building off the work of the Responsible AI team that first formed in 2018 to publish "Facebook’s five pillars of Responsible AI" (Meta, 2021).

Comparison with other governance mechanisms

Although the current move is towards having state-wide legislation to regulate AI applications, there are other possible ways of moving forward, such as legislating a reduction in AI usage and requiring more humans in the process.

Even as Facebook has made its moves towards trying to have AI moderate more and more content over time, it has continued to employ more human content reviewers as well, with 15,000 content reviewers employed by the end of 2018 (Meta, 2018b). Following the 2016 US elections, Facebook also began working with external fact-checking partners to fact-check trending stories globally (Mosseri, 2016).

Another option is 'co-governance' - more of a middle-ground between self-governing and external regulation - "such models seek to provide some values of democratic accountability without making extreme changes to the status quo" (Gorwa, 2019b). Co-governance would require a more collaborative approach between Meta and other important stakeholders such as regulatory bodies and users.

It should be noted that there are already some ongoing efforts in this vein, with Meta taking part in several multi-company forums over recent years, including the "EU Internet Forum" in 2014 and the "Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism" in 2017, both focussed around tackling hate speech and illegal content on the site. In 2018, the "High-Level Expert Group on Fake News and Disinformation" created the "Code of Practice on Online Disinformation", which Facebook signed alongside other large social media companies and advertising associations.

A short-lived experiment but perhaps one that could be tried again at some point, was the idea of users themselves casting votes on policy changes at Facebook, which they tried in 2012 but received a mere 0.038 percent participation, whereas they were aiming for 30% of users to vote to make the veto binding (Gillespie, 2018).

Regulation could also focus less on the timelines and requirements around content takedowns, and more on transparency of how AI is being used in these efforts - what models are used, what sort of data is prioritised for takedown, how models are improved etc. However, some think that true transparency is not possible to achieve "Pursuing views into a system’s inner workings is not only inadequate, it creates a “transparency illusion” promising consequential accountability that transparency cannot deliver" (Ananny & Crawford, 2018), and others rightly point out that historical efforts to invoke transparency as a way to shame companies into behaving better has not had a huge effect when it comes to changing behaviour, or as Ananny and Crawford put it - "Power that comes from special, private interests driven by commodification of people’s behaviors may ultimately be immune to transparency" (Ananny & Crawford, 2018).

Outside of regulatory action, there can also be a more citizen-led push towards better standards - Karatani argues for consumption as the space in capitalism where workers can exert pressure through boycotting products (Karatani, 2005), and Fuchs argues for striking as an effective way to exert pressure on companies through boycotting production and causing financial harm to the company (Fuchs, 2012). We have seen this latter playout recently when Facebook employees conducted a 'virtual walkout' in 2020 following Facebook's decision to leave up posts that Twitter had removed for 'glorifying violence' (Newton, 2020). Dutton and Dubois also suggest a similarly public-driven approach to governance on the internet - "pluralistic accountability", where civil society actors play a significant role in the governance of digital platforms (Dutton & Dubois, 2015).

Conclusion

We can see that Meta has largely been self-regulating its use of AI for content moderation on Facebook (and indeed its tech in general) and has certainly made a lot of changes over the last 5 years to do the majority of content moderation in an automated way in order to tackle the problem of scale, but has also introduced some measures which are much more human-focussed such as the Oversight Board.

With recent regulation starting to tackle these things, and upcoming regulation by other global players, we can see that the days of self-regulation are coming to an end for Meta, and going forward we will likely see more efforts towards embracing co-governance in order for Meta to implement changes on their platforms without having no say in the regulation that it is subject to.

Bibliography

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2021). The governance triangle: Regulatory standards institutions and the shadow of the state. In_The Spectrum of International Institutions_ (pp. 52–91). Routledge.

Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2018). Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability.New Media & Society,20(3), 973–989.

Andersson Schwarz, J. (2017). Platform logic: An interdisciplinary approach to the platform‐based economy.Policy & Internet,9(4), 374–394.

Andreessen, M. (2007). The three kinds of platforms you meet on the Internet.Blog. Pmarca. Com.

Andriole, S. (n.d.).Already Too Big To Fail—The Digital Oligarchy Is Alive, Well (& Growing). Forbes. Retrieved 8 January 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/steveandriole/2017/07/29/already-too-big-to-fail-the-digital-oligarchy-is-alive-well-growing/

Atal, M. R. (2020). The Janus faces of silicon valley.Review of International Political Economy,28(2), 336–350.

Bowker, G., & Star, S. (1994).Bowker, G." Information Mythology and Infrastructure.» In Information Acumen: The Understanding and Use of Knowledge in Modem Business, edited by L. Bud.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship.Journal of Computer‐mediated Communication,13(1), 210–230.

Clegg, N. (2020, May 6). Welcoming the Oversight Board.Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2020/05/welcoming-the-oversight-board/

Cobbe, J. (2021). Algorithmic censorship by social platforms: Power and resistance.Philosophy & Technology,34(4), 739–766.

Correlating Eugenics (Chapter 1). (2021). In W. H. K. Chun,Discriminating data: Correlation, neighborhoods, and the new politics of recognition. The MIT Press.

Dutton, W. H., & Dubois, E. (2015). The Fifth Estate: A rising force of pluralistic accountability. In_Handbook of digital politics_ (pp. 51–66). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power.Critical Inquiry,8(4), 777–795.

Fuchs, C. (2012). The political economy of privacy on Facebook.Television & New Media,13(2), 139–159.

Garton Ash, T., Gorwa, R., & Metaxa, D. (2019).Glasnost! Nine ways Facebook can make itself a better forum for free speech and democracy.

Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’.New Media & Society,12(3), 347–364.

Gillespie, T. (2015).Platforms Intervene. Social Media & Society, 1–2.

Gillespie, T. (2017). Regulation of and by Platforms.The SAGE Handbook of Social Media.

Gillespie, T. (2018).Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Goldman, R. (2017, October 27). Update on Our Advertising Transparency and Authenticity Efforts.Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2017/10/update-on-our-advertising-transparency-and-authenticity-efforts/

Gorwa, R. (2019a). The platform governance triangle: Conceptualising the informal regulation of online content.Internet Policy Review,8(2), 1–22.

Gorwa, R. (2019b). What is platform governance?Information, Communication & Society,22(6), 854–871.

Helberger, N., Pierson, J., & Poell, T. (2018). Governing online platforms: From contested to cooperative responsibility.The Information Society,34(1), 1–14.

Helmond, A. (2015). The platformization of the web: Making web data platform ready.Social Media+ Society,1(2), 2056305115603080.

Karatani, K. (2005).Transcritique: On Kant and Marx. Mit Press.

Kirkpatrick, D. (2011).The Facebook effect: The inside story of the company that is connecting the world. Simon and Schuster.

Kleis Nielsen, R., & Ganter, S. A. (2018). Dealing with digital intermediaries: A case study of the relations between publishers and platforms.New Media & Society,20(4), 1600–1617.

Kreiss, D., & McGregor, S. C. (2018). Technology firms shape political communication: The work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and Google with campaigns during the 2016 US presidential cycle.Political Communication,35(2), 155–177.

Langlois, G., & Elmer, G. (2013). The research politics of social media platforms.Culture Machine,14.

Lessig, L. (2009).Code: And other laws of cyberspace. ReadHowYouWant. com.

Lianos, M. (2012).The new social control: The institutional web, normativity and the social bond. Red Quill Books.

Liu, A. (2004). Transcendental data: Toward a cultural history and aesthetics of the new encoded discourse.Critical Inquiry,31(1), 49–84.

MacKinnon, R., Hickok, E., Bar, A., & Lim, H. (2015).Fostering freedom online: The role of internet intermediaries. UNESCO Publishing.

Malik, N. (2022, January 20).How Facebook took over the internet in Africa – and changed everything. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jan/20/facebook-second-life-the-unstoppable-rise-of-the-tech-company-in-africa

Manjoo, F. (2016). Why the world is drawing battle lines against American tech giants.The New York Times.

Meta. (n.d.-a).Community Standards Enforcement | Transparency Center. Retrieved 8 January 2023, from https://transparency.fb.com/data/community-standards-enforcement/

Meta. (n.d.-b).Facebook Community Standards | Transparency Centre. Retrieved 8 January 2023, from https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/

Meta. (2017, June 15). Introducing Hard Questions.Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2017/06/hard-questions/

Meta. (2018a, April 6). Making Ads and Pages More Transparent.Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2018/04/transparent-ads-and-pages/

Meta. (2018b, July 26). Hard Questions: Who Reviews Objectionable Content on Facebook — And Is the Company Doing Enough to Support Them?Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2018/07/hard-questions-content-reviewers/

Meta. (2018c, November 6). An Independent Assessment of the Human Rights Impact of Facebook in Myanmar.Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2018/11/myanmar-hria/

Meta. (2020a, June 15).Collaborating on the future of AI governance in the EU and around the world. https://ai.facebook.com/blog/collaborating-on-the-future-of-ai-governance-in-the-eu-and-around-the-world/

Meta. (2020b, September 19).How AI is getting better at detecting hate speech. https://ai.facebook.com/blog/how-ai-is-getting-better-at-detecting-hate-speech/

Meta. (2021, June 22).Facebook’s five pillars of Responsible AI. https://ai.facebook.com/blog/facebooks-five-pillars-of-responsible-ai/

Mosseri, A. (2016, December 15). Addressing Hoaxes and Fake News.Meta. https://about.fb.com/news/2016/12/news-feed-fyi-addressing-hoaxes-and-fake-news/

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Digital news report.Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Newton, C. (2019, October 2).The world responds to the Zuckerberg leak. (Also: More leaking). https://www.getrevue.co/profile/caseynewton/issues/the-world-responds-to-the-zuckerberg-leak-also-more-leaking-202477

Newton, C. (2020, June 2).What Facebook doesn’t understand about the Facebook walkout. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/interface/2020/6/1/21276969/facebook-walkout-mark-zuckerberg-audio-trump-disgust-twitter

Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity.New Media & Society,20(11), 4275–4292.

Oversight Board. (n.d.).Decision | Oversight Board. Retrieved 8 January 2023, from https://www.oversightboard.com/decision/

Plantin, J.-C., Lagoze, C., Edwards, P. N., & Sandvig, C. (2018). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook.New Media & Society,20(1), 293–310.

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & Van Dijck, J. (2018). Platform power & public value.AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research.

Ruggie, J. G. (2007). Business and human rights: The evolving international agenda.American Journal of International Law,101(4), 819–840.

Sandvig, C. (2013).The Internet as infrastructure.

Santa Clara Principles. (2018).Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation. Santa Clara Principles. https://santaclaraprinciples.org/

Sen, R., Ahmad, S., Phokeer, A., Farooq, Z. A., Qazi, I. A., Choffnes, D., & Gummadi, K. P. (2017). Inside the walled garden: Deconstructing Facebook’s free basics program.ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review,47(5), 12–24.

Siapera, E., & Viejo-Otero, P. (2021). Governing hate: Facebook and digital racism.Television & New Media,22(2), 112–130.

Snow, J. (2018, April 27).…It’s much easier to build an AI system that can detect a nipple than it is to determine what is linguistically hate speech. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2018/04/27/143182/its-easier-to-build-an-ai-system-to-detect-a-nipple-than-what-is-hate-speech/

Star, S. L., & Ruhleder, K. (1994). Steps towards an ecology of infrastructure: Complex problems in design and access for large-scale collaborative systems.Proceedings of the 1994 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 253–264.

Suzor, N., Van Geelen, T., & Myers West, S. (2018). Evaluating the legitimacy of platform governance: A review of research and a shared research agenda.International Communication Gazette,80(4), 385–400.

UK Parliament. (2019).Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Final Report published - Committees - UK Parliament. https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/378/digital-culture-media-and-sport-committee/news/103668/disinformation-and-fake-news-final-report-published/

Van Dijck, J. (2013).The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

Van Dijck, J., de Winkel, T., & Schäfer, M. T. (2021). Deplatformization and the governance of the platform ecosystem.New Media & Society, 14614448211045662.

Van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding social media logic.Media and Communication,1(1), 2–14.

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018).The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press.

Vincent, J. (2016, February 8).Facebook’s Free Basics service has been banned in India. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2016/2/8/10913398/free-basics-india-regulator-ruling

Zuckerberg, M. (2021, May 5).A Blueprint for Content Governance and Enforcement.